Kodokan Judo

柔道

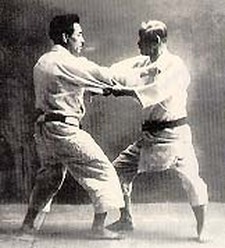

Kyuzo Mifune (left) and Jigoro Kano (left)

The Kodokan Judo (柔道 jūdō, meaning "gentle way") is a modern martial art, combat and Olympic sport created in Japan in 1882 by Jigoro Kano (嘉納治五郎).

Its most prominent feature is its competitive element, where the objective is to either throw or takedown an opponent to the ground, immobilize or otherwise subdue an opponent with a pin, or force an opponent to submit with a joint lock or achoke. Strikes and thrusts by hands and feet as well as weapons defenses are a part of judo, but only in pre-arranged forms (kata, 形) and are not allowed in judo competition or free practice (randori, 乱取り). A judo practitioner is called a judoka. The philosophy and subsequent pedagogy developed for judo became the model for other modern Japanese martial arts that developed from koryū (古流, traditional schools). The worldwide spread of judo has led to the development of a number of offshoots such as Sambo and Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

Early life of Jigoro Kano - Founder of Kodokan Judo -

The early history of judo is inseparable from its founder, Japanese polymath and educator Jigoro Kano (嘉納 治五郎 Kanō Jigorō, 1860–1938), born Shinnosuke Kano (嘉納 新之助 Kanō Shinnosuke?). Kano was born into a relatively affluent family. His father, Jirosaku, was the second son of the head priest of the Shinto Hiyoshi shrine in Shiga Prefecture. He married Sadako Kano, daughter of the owner of Kiku-Masamune sake brewing company and was adopted by the family, changing his name to Kano, and ultimately became an official in the Shogunal government.

Jigoro Kano had an academic upbringing and, from the age of seven, he studied English, Japanese calligraphy (書道 shodō?) and theFour Confucian Texts (四書 Shisho?) under a number of tutors. When he was fourteen, Kano began boarding at an English-medium school, Ikuei-Gijuku in Shiba, Tokyo. The culture of bullying endemic at this school was the catalyst that caused Kano to seek out a Jujutsu(柔術 Jūjutsu) dojo (道場 dōjō, training place) at which to train.

Early attempts to find a jujutsu teacher who was willing to take him on met with little success. With the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in the Meiji Restoration of 1868, jujutsu had become unfashionable in an increasingly westernised Japan. Many of those who had once taught the art had been forced out of teaching or become so disillusioned with it that they had simply given up. Nakai Umenari, an acquaintance of Kanō's father and a former soldier, agreed to show him kata, but not to teach him. The caretaker of Jirosaku's second house, Katagiri Ryuji, also knew jujutsu, but would not teach it as he believed it was no longer of practical use. Another frequent visitor, Imai Genshiro of Kyūshin-ryū (扱心流) school of jujutsu, also refused. Several years passed before he finally found a willing teacher.

In 1877, as a student at the Tokyo-Kaisei school (soon to become part of the newly founded Tokyo Imperial University), Kano learned that many jujutsu teachers had been forced to pursue alternative careers, frequently opening Seikotsu-in (整骨院), traditional osteopathy practices).[6] After inquiring at a number of these, Kano was referred to Fukuda Hachinosuke (c.1828–1880),[7] a teacher of the Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū (天神真楊流) of jujutsu, who had a small nine mat dojo where he taught five students.[8] Fukuda is said to have emphasized technique over formal exercise, sowing the seeds of Kano's emphasis on randori (乱取り randori), free practice) in judo.

On Fukuda's death in 1880, Kano, who had become his keenest and most able student in both randori and kata (形 kata, pre-arranged forms), was given the densho (伝書?, scrolls) of the Fukuda dojo. Kano chose to continue his studies at another Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū school, that of Iso Masatomo (c.1820–1881). Iso placed more emphasis on the practice of "kata", and entrusted randori instruction to assistants, increasingly to Kano. Iso died in June 1881 and Kano went on to study at the dojo of Iikubo Tsunetoshi (1835–1889) of Kitō-ryū (起倒流). Like Fukuda, Iikubo placed much emphasis on randori, with Kitō-ryū having a greater focus on nage-waza (投げ技, throwing techniques).

Founding of the Kodokan Institute -

Eisho-ji Temple, Tokyo.

In February 1882, Kano founded a school and dojo at the Eisho-ji (永昌寺), a Buddhist temple in what was then the Shitaya ward of Tokyo (now the Higashi Ueno district of Taitō ward). Iikubo, Kano's Kitō-ryū instructor, attended the dojo three days a week to help teach and, although two years would pass before the temple would be called by the name Kodokan (講道館 Kōdōkan, "place for expounding the way"), and Kano had not yet received his Menkyo (免許, certificate of mastery) in Kitō-ryū, this is now regarded as the Kodokan founding.

The Eisho-ji dojo was a relatively small affair, consisting of a twelve mat training area. Kano took in resident and non-resident students, the first two being Tsunejiro Tomita and Shiro Saigo. In August, the following year, the pair were granted shodan (初段, first rank)grades, the first that had been awarded in any martial art.

Judo versus Jujutsu -

"Judo" (柔道 jūdō), Central to Kano's vision for judo were the principles of seiryoku zen'yō (精力善用, maximum efficiency, minimum effort) and jita kyōei (自他共栄, mutual welfare and benefit). He illustrated the application of seiryoku zen'yō with the concept of jū yoku gō o seisu (柔よく剛を制す, softness controls hardness):

In short, resisting a more powerful opponent will result in your defeat, whilst adjusting to and evading your opponent's attack will cause him to lose his balance, his power will be reduced, and you will defeat him. This can apply whatever the relative values of power, thus making it possible for weaker opponents to beat significantly stronger ones. This is the theory of ju yoku go o seisu. Kano realized that seiryoku zen'yō, initially conceived as a jujutsu concept, had a wider philosophical application. Coupled with the Confucianist-influenced jita kyōei, the wider application shaped the development of judo from a martial art (武術 bujutsu) to a martial way (武道 budō). Kano rejected techniques that did not conform to these principles and emphasised the importance of efficiency in the execution of techniques. He was convinced that practice of jujutsu while conforming to these ideals was a route to self-improvement and the betterment of society in general. He was, however, acutely conscious of the Japanese public's negative perception of jujutsu:

At the time a few bujitsu (martial arts) experts still existed but bujitsu was almost abandoned by the nation at large. Even if I wanted to teach jujitsu most people had now stopped thinking about it. So I thought it better to teach under a different name principally because my objectives were much wider than jujitsu. Kano believed that "jūjutsu" was insufficient to describe his art: although Jutsu (術) means "art" or "means", it implies a method consisting of a collection of physical techniques. Accordingly, he changed the second character to dō (道), meaning way, road or path, which implies a more philosophical context than jutsu and has a common origin with the Chinese concept of tao. Thus Kano renamed it judo (柔道 Jūdō).

Judo waza (techniques) See also: Judo techniques and List of Kodokan judo techniques

There are three basic categories of waza (技, techniques) in judo: nage-waza (投げ技, throwing techniques), katame-waza (固技), grappling techniques) and atemi-waza (当て身技, striking techniques). Judo is most known for nage-waza and katame-waza.

Judo practitioners typically devote a portion of each practice session to ukemi (受け身, break-falls), in order that nage-waza can be practiced without significant risk of injury. Several distinct types of ukemi exist, including ushiro ukemi (後ろ受身?, rear breakfalls); yoko ukemi (横受け身, side breakfalls); mae ukemi (前受け身, front breakfalls); and zenpo kaiten ukemi (前方回転受身), rolling breakfalls)

The person who performs a Waza is known as tori (取り, literally "taker") and the person to whom it is performed is known as uke (受け, literally "receiver").

柔道

Kyuzo Mifune (left) and Jigoro Kano (left)

The Kodokan Judo (柔道 jūdō, meaning "gentle way") is a modern martial art, combat and Olympic sport created in Japan in 1882 by Jigoro Kano (嘉納治五郎).

Its most prominent feature is its competitive element, where the objective is to either throw or takedown an opponent to the ground, immobilize or otherwise subdue an opponent with a pin, or force an opponent to submit with a joint lock or achoke. Strikes and thrusts by hands and feet as well as weapons defenses are a part of judo, but only in pre-arranged forms (kata, 形) and are not allowed in judo competition or free practice (randori, 乱取り). A judo practitioner is called a judoka. The philosophy and subsequent pedagogy developed for judo became the model for other modern Japanese martial arts that developed from koryū (古流, traditional schools). The worldwide spread of judo has led to the development of a number of offshoots such as Sambo and Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

Early life of Jigoro Kano - Founder of Kodokan Judo -

The early history of judo is inseparable from its founder, Japanese polymath and educator Jigoro Kano (嘉納 治五郎 Kanō Jigorō, 1860–1938), born Shinnosuke Kano (嘉納 新之助 Kanō Shinnosuke?). Kano was born into a relatively affluent family. His father, Jirosaku, was the second son of the head priest of the Shinto Hiyoshi shrine in Shiga Prefecture. He married Sadako Kano, daughter of the owner of Kiku-Masamune sake brewing company and was adopted by the family, changing his name to Kano, and ultimately became an official in the Shogunal government.

Jigoro Kano had an academic upbringing and, from the age of seven, he studied English, Japanese calligraphy (書道 shodō?) and theFour Confucian Texts (四書 Shisho?) under a number of tutors. When he was fourteen, Kano began boarding at an English-medium school, Ikuei-Gijuku in Shiba, Tokyo. The culture of bullying endemic at this school was the catalyst that caused Kano to seek out a Jujutsu(柔術 Jūjutsu) dojo (道場 dōjō, training place) at which to train.

Early attempts to find a jujutsu teacher who was willing to take him on met with little success. With the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in the Meiji Restoration of 1868, jujutsu had become unfashionable in an increasingly westernised Japan. Many of those who had once taught the art had been forced out of teaching or become so disillusioned with it that they had simply given up. Nakai Umenari, an acquaintance of Kanō's father and a former soldier, agreed to show him kata, but not to teach him. The caretaker of Jirosaku's second house, Katagiri Ryuji, also knew jujutsu, but would not teach it as he believed it was no longer of practical use. Another frequent visitor, Imai Genshiro of Kyūshin-ryū (扱心流) school of jujutsu, also refused. Several years passed before he finally found a willing teacher.

In 1877, as a student at the Tokyo-Kaisei school (soon to become part of the newly founded Tokyo Imperial University), Kano learned that many jujutsu teachers had been forced to pursue alternative careers, frequently opening Seikotsu-in (整骨院), traditional osteopathy practices).[6] After inquiring at a number of these, Kano was referred to Fukuda Hachinosuke (c.1828–1880),[7] a teacher of the Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū (天神真楊流) of jujutsu, who had a small nine mat dojo where he taught five students.[8] Fukuda is said to have emphasized technique over formal exercise, sowing the seeds of Kano's emphasis on randori (乱取り randori), free practice) in judo.

On Fukuda's death in 1880, Kano, who had become his keenest and most able student in both randori and kata (形 kata, pre-arranged forms), was given the densho (伝書?, scrolls) of the Fukuda dojo. Kano chose to continue his studies at another Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū school, that of Iso Masatomo (c.1820–1881). Iso placed more emphasis on the practice of "kata", and entrusted randori instruction to assistants, increasingly to Kano. Iso died in June 1881 and Kano went on to study at the dojo of Iikubo Tsunetoshi (1835–1889) of Kitō-ryū (起倒流). Like Fukuda, Iikubo placed much emphasis on randori, with Kitō-ryū having a greater focus on nage-waza (投げ技, throwing techniques).

Founding of the Kodokan Institute -

Eisho-ji Temple, Tokyo.

In February 1882, Kano founded a school and dojo at the Eisho-ji (永昌寺), a Buddhist temple in what was then the Shitaya ward of Tokyo (now the Higashi Ueno district of Taitō ward). Iikubo, Kano's Kitō-ryū instructor, attended the dojo three days a week to help teach and, although two years would pass before the temple would be called by the name Kodokan (講道館 Kōdōkan, "place for expounding the way"), and Kano had not yet received his Menkyo (免許, certificate of mastery) in Kitō-ryū, this is now regarded as the Kodokan founding.

The Eisho-ji dojo was a relatively small affair, consisting of a twelve mat training area. Kano took in resident and non-resident students, the first two being Tsunejiro Tomita and Shiro Saigo. In August, the following year, the pair were granted shodan (初段, first rank)grades, the first that had been awarded in any martial art.

Judo versus Jujutsu -

"Judo" (柔道 jūdō), Central to Kano's vision for judo were the principles of seiryoku zen'yō (精力善用, maximum efficiency, minimum effort) and jita kyōei (自他共栄, mutual welfare and benefit). He illustrated the application of seiryoku zen'yō with the concept of jū yoku gō o seisu (柔よく剛を制す, softness controls hardness):

In short, resisting a more powerful opponent will result in your defeat, whilst adjusting to and evading your opponent's attack will cause him to lose his balance, his power will be reduced, and you will defeat him. This can apply whatever the relative values of power, thus making it possible for weaker opponents to beat significantly stronger ones. This is the theory of ju yoku go o seisu. Kano realized that seiryoku zen'yō, initially conceived as a jujutsu concept, had a wider philosophical application. Coupled with the Confucianist-influenced jita kyōei, the wider application shaped the development of judo from a martial art (武術 bujutsu) to a martial way (武道 budō). Kano rejected techniques that did not conform to these principles and emphasised the importance of efficiency in the execution of techniques. He was convinced that practice of jujutsu while conforming to these ideals was a route to self-improvement and the betterment of society in general. He was, however, acutely conscious of the Japanese public's negative perception of jujutsu:

At the time a few bujitsu (martial arts) experts still existed but bujitsu was almost abandoned by the nation at large. Even if I wanted to teach jujitsu most people had now stopped thinking about it. So I thought it better to teach under a different name principally because my objectives were much wider than jujitsu. Kano believed that "jūjutsu" was insufficient to describe his art: although Jutsu (術) means "art" or "means", it implies a method consisting of a collection of physical techniques. Accordingly, he changed the second character to dō (道), meaning way, road or path, which implies a more philosophical context than jutsu and has a common origin with the Chinese concept of tao. Thus Kano renamed it judo (柔道 Jūdō).

Judo waza (techniques) See also: Judo techniques and List of Kodokan judo techniques

There are three basic categories of waza (技, techniques) in judo: nage-waza (投げ技, throwing techniques), katame-waza (固技), grappling techniques) and atemi-waza (当て身技, striking techniques). Judo is most known for nage-waza and katame-waza.

Judo practitioners typically devote a portion of each practice session to ukemi (受け身, break-falls), in order that nage-waza can be practiced without significant risk of injury. Several distinct types of ukemi exist, including ushiro ukemi (後ろ受身?, rear breakfalls); yoko ukemi (横受け身, side breakfalls); mae ukemi (前受け身, front breakfalls); and zenpo kaiten ukemi (前方回転受身), rolling breakfalls)

The person who performs a Waza is known as tori (取り, literally "taker") and the person to whom it is performed is known as uke (受け, literally "receiver").